Link

to Wikipedia entry for

Catheryna

Rombout Brett

Link

to Wikipedia entry for

The

Madame Brett Homestead

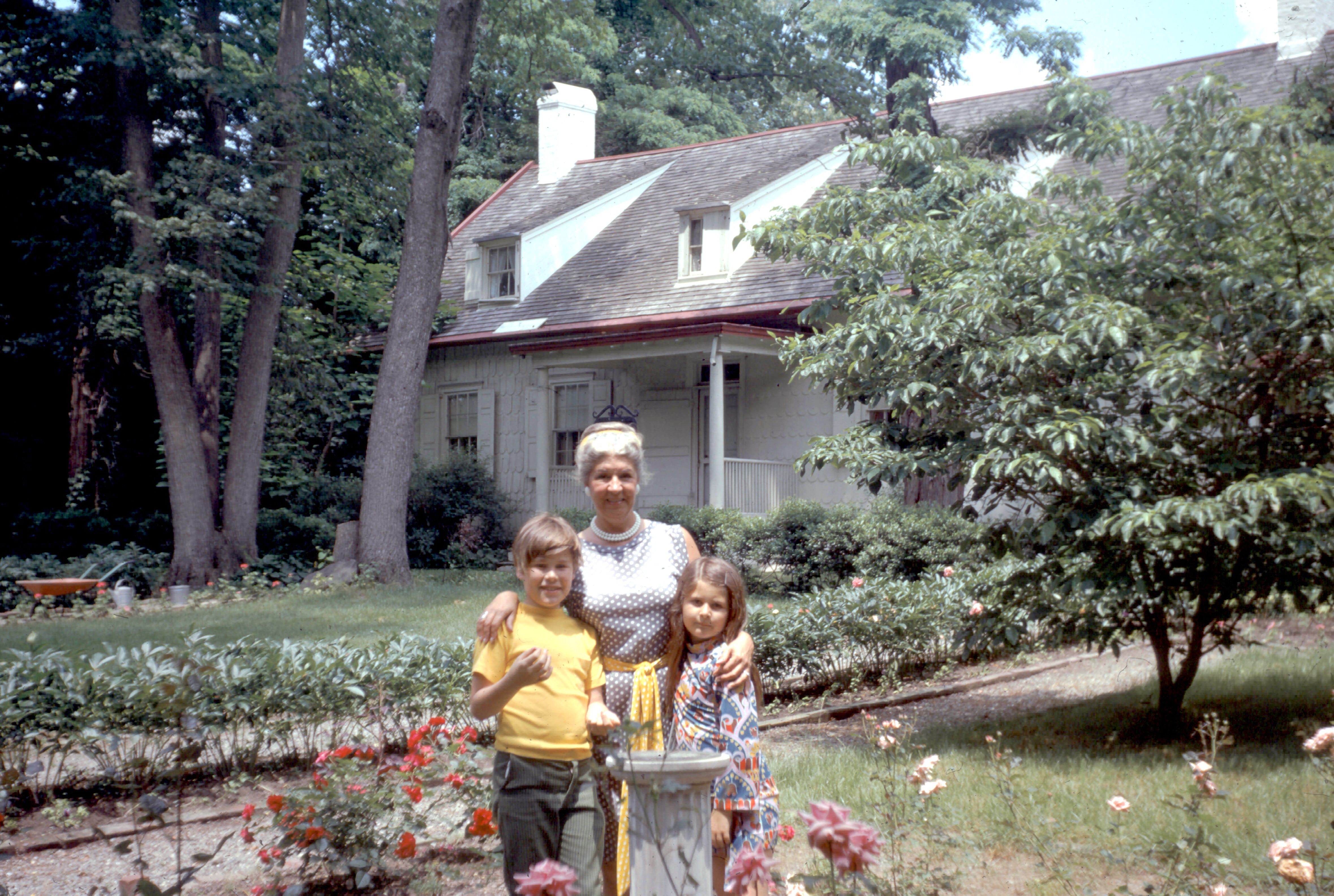

William

IV, Florence Elizabeth and Graceanne at

Madame Brett's

house - 1967 Madame Brett was William IV's

13th Great

Grandmother

Most if not all histories of

the history of Dutchess County, New York, and in particular of

the town of Fishkill, make early and frequent mention of Catharyna

Rombouts (often referred to later as "Madame Brett"

-- but her story begins with her baptism on 25 May 1687 in New

York City, the daughter of Francis Rombouts and Helena Teller.

Family Background

Catharyna's parents had each

been married twice before their union, and her mother had quite

a few children from her prior marriages. Francis (originally François)

Rombouts, a Walloon born in the Bishpric of Liège, who

came to New Netherland as supercargo on a Dutch West India Company

shipment, became a prosperous merchant, alderman of New York City

and in 1679 the city's twelfth mayor. Helena Teller was the daughter

of William Teller, a prosperous merchant himself in Albany, who

had arrived in very similar circumstances, though of ethnically

Dutch German ancestry and born in Scotland.

The Rombout Patent

A few years before Catharyna

was born, Francis and two partners had made an agreement with

the indigenous Wappinger confederation to purchase a tract of

land on the east side of the Hudson River in what would soon be

defined by the Province as Dutchess County. This was called the

Rombout Patent after the British subjects' right to own the land

was confirmed in 1685. The land covered about 85,000 acres, and

no European settlement to speak of had taken place there. It was,

to them, utter wilderness, and a good number of indigenous people

not party to the agreement with the Europeans remained, a potential

(and soon to be real) precursor of violence. Francis and his partners

probably planned to trap animals for fur on the land, but they

did not act immediately, and then they began to die.

Francis probably didn't expect

his wife to have any use for this land in her lifetime, and his

other children had died young. Thus, in 1691, as he took ill and

anticipated his death, he recorded a will, in which he devised

that his one-third share in the Rombout Patent, as well as his

home in the City, go to Catharyna, to be hers upon reaching the

age of majority or marrying. After two codicils which resulted

in some clarifications and an increase of the share of his other

assets that his wife would receive (to 4,000 guilders). By April

21st, 1691, he had died. Eventually see Francis Rombout's profile

for details and evidence of the above.

Marriage and Life in New York

City

By 1703, Catharyna was sixteen

years old, and by license dated 25 November of that year, she

married Roger Brett, said to be a lieutenant in the Royal Navy

who may have been of an aristocratic family, who was an acquaintance

and perhaps even a friend of the province's new governor, Lord

Cornbury. It has additionally been asserted that Roger had arrived

with Lord Cornbury upon his appointment in 1701 as governor of

the neighboring Province of New Jersey.

Catharyna and Roger began a

family in the ensuing years, almost certainly living in the Rombouts

estate on Broadway (formerly Heere Straat under Dutch rule), and

perhaps with her mother. The estate extended to the Hudson River,

and was described as "the handsomest of them all," with

"picturesque gardens".

Probate and Patent Land Division

Catharyna's thrice-widowed

mother died in 1707. Although her father had been quite generous

to Catharyna in his will, her mother seems not to have been so.

She willed that Catharyna would receive from her a mere nine pence,

her other assets divided between children and grandchildren from

her earlier marriages. This might have been a slight, but it also

might have reflected her expectation that her other children had

more use for additional property, given Catharyna's inheritance

from her father, and her marriage to a man with an excellent connection

in government.

Helena's other act of consequence

to our story was a non-action -- she apparently did not fully

execute her husband's will to the satisfaction of Catharyn and

Roger. What that might have entailed is not clear. It seems that

at this time, there was a 1/3 share in a land that was unsettled,

and that no one had taken any action to decide how the shares

would translate to boundaries within the patented land. Helena

may have done nothing, but no one else had, either.

Nonetheless, when she died

in 1707, Francis Rombout's estate was deemed unsettled, and Lord

Cornbury conveniently appointed Roger Brett to finish the job,

"the estate not having been fully administered upon by the

widow," according to an abstract. Roger and Catharyn might

have had some intent to find a way to receive other assets, or

perhaps Roger was just the right person to handle the settlement

of the estate given that the land was the remaining matter.

In Dutchess County

It does seem that the Bretts

seized executorship in order to do something with the land. By

petition, the Bretts and the heirs to the other two thirds of

the patent achieved a partition in 1708, setting the stage for

some form of settlement to begin.

Unlike others who came into

large tracts of land in Dutchess County, who simply entered into

leases with tenant farmers as absentee landlords, the Bretts moved

in.

They must have almost immediately

built a mill near where Fishkill Creek contributes to the Hudson

River in 1708, they mortgaged land in 1709 to raise additional

funds, and they did also begin to place tenant farmers on lots.[6]

It is believed they built their home, which today is the oldest

building still standing in Dutchess County, in 1709. The mill

was a vital ingredient, as the farmers, who by-and-large raised

wheat, were best served by processing it locally -- and if the

Bretts did the processing, then of course their share of the profit

from the land was further increased.

This area came to be known

as Matteawan, which was later subsumed by Fishkill and eventually

carved out as part of Beacon, New York.

The Bretts lived, during this

time, in both the City and Matteawan. The Kings Highway into the

area being but muddy trail, they would sail by sloop up and down

the Hudson. In fact, their fourth child is said to have been named

Rivery because he was born on the river.

Around 1716, it seems that

whomever was at the helm of the sloop on which Roger stood as

he approached Fishkill Landing misjudged the weather. A gust caught

the sail and apparently the ensuing flying jibe caught Roger unaware.

The boom struck him in the head, sending him into the water where

he drowned -- a tragic and somewhat inglorious end to the life

of an officer of the Royal Navy, who might have looked forward

to his later days as a leader of the budding Fishkill community.

Catharyna suddenly found herself

in the wilderness with no husband and three children.

At this point, we ought to

remind ourselves that, as a woman in 1716, many would have expected

Catharyna to retreat to the City and/or at least to remarry quickly.

But she did neither. Instead, in cooperation with George Clarke,

Secretary of the Province of New York and the grantee of a large

mortgage by the Bretts on which they had funded their early activities,

she recruited wealthy friends and family from the City and Long

Island to purchase lots of the land that had been mortgaged, and

eventually paid back George Clarke through these transactions.

One example is their sale of 959 acres to Cornelius van Wyck.

Catharyna and others developed

Fishkill into a hub of agricultural activity, and her mill was

in the center of the action. People in town may have begun to

refer to her as Madame Brett in these years, although some argue

that this reference came from historians who felt compelled to

"dress her up."

Regardless of what they called

her, if Fishkill had a business leader, it was Catharyna Brett.

Late in her years, and in addition

to running the mill, dealing in and letting real estate, and running

the family farm, Catharyna led the creation of a partnership to

found the Frankfort Store House at Fishkill Landing in 1743. The

storehouse served as the way-point for goods to come and go from

the Fishkill area and further solidified the town's role as a

hub of commerce. This storehouse, and most of Fishkill, in fact,

played a vital role in the Revolutionary War over four decades

later.

Only one of the Bretts' children

survived her. In her will, executed and proved in 1763, she devised

portions of her land holdings to go to her older son Francis,

that he might eventually allocate them to his children, and she

allocated smaller properties individually to a number of her grandchildren

by her son Robert.

Catharyna died in the Spring

of 1764, and was buried in the Dutch Reformed Church in Fishkill

near the pulpit. A plaque honoring her is mounted in the church.